On Crossing No Horizon:

Reflecting on the inspiration for “Cross No Horizon”.April 2024

In 2019, I along with many other artists, activists, organizers and community members started Creatives for Asylum Seekers and Migrants, or CASM. This was a largely reactionary evocation of the consolidation of community power, spurred by the inhumane treatment of persons who had made a very costly, oftentimes perilous and dangerous journey from Central America to the Texas border. It was imperative, we felt, that we as persons, who as a collective, had means and resources, to utilize those to address the harm those migrating were facing within our state and local community. Through our action, an art auction, we were able to raise nearly $8,000 which was donated to Houston Immigration Legal Services Collaborative, or HILSC.

It’s been nearly five years since CASM has been active, in fact, we managed to only complete a single operation. However, I have never stopped feeling as strongly as I had about the unjust and oftentimes inhumane and dehumanizing ways these persons have been treated, represented and engaged by our government.

When I was approached by Aurora Picture Show Curator Salome Kokoladze to participate in Night Light 2024, I honestly thought to myself, “Why me, I don’t even do projections?” A statement that was not entirely true, though I tried to convince myself of its validity. Before I could say no, I said yes, because it would be an opportunity to showcase my capacity to expand my artistic practice. I did not have an idea for the engagement, but knew that once I saw the space I would allow myself to imagine possibilities. Upon arriving on location and viewing my canvas I immediately was drawn to the phrase CROSS NO HORIZONS, which was stenciled on the bayou walls, just above the water line. The phrase, in my opinion, was very loaded. Particularly so, because at the time of my site visit there were news reports of an incoming caravan of migrants from Central American countries passing through Mexico and approaching the Texas border.

I felt that same uneasiness I experienced when CASM was formed. I knew I wanted to share their stories, their experiences, the things they were escaping, the prices paid, the trauma, danger and uncertainty of their ability to succeed in their quest, but the determination to find out whether their desired future lay just over the horizon. I personally know several undocumented immigrants, and they are some of the best and brightest persons I have met in my life. I knew that I certainly did not want to compromise them and their status here in the United States, but I did want to show up for them as an ally and someone that may not be able to identify, but could totally empathize and understand what America appears to be from the outside and how it has played an active role in destabilizing many of the countries, territories and communities that many immigrants are fleeing. I also had to acknowledge that I could not encapsulate the varied experiences of all immigrants in a single project. So I made the choice to choose just one mode of transit: La Bestia (“The Beast”), also known as El Tren de la Muerte ("The Train of Death") and El Tren de los Desconocidos ("The Train of the Unknowns"). La Bestia is a freight train that starts its route in Chiapas state in southern Mexico, near the border of Guatemala. From there it travels north to the Lecherías station on the outskirts of Mexico City, where it connects with a network of Mexican freight trains heading to different points on the U.S. border.

In preparation for this piece I watched several documentaries, news stories, YouTube videos, and read as much as I could in the short period of time I had to produce this artwork. I am in no way a scholar on the matter and would not pass myself off as one. If anything, I am an interested party seeking ways in which I can educate myself well enough to be an effective advocate for the train’s passengers through creative means.

Acknowledging the risk an individual would be taking in sharing either a familial, or personal experience whether through video or audio, I chose instead to utilize the visuals and audio I had been exposed to while preparing for the project. Even then, I still felt as if I was making those that had been interviewed, filmed or documented vulnerable. I decided that I would not show the direct references, but make space for them to share their experiences in their own words.

There are two versions of the same piece, the first of which was redone to adjust for the site and the lighting conditions; this not at the behest of, but in acknowledgement of Salome’s critique on the amount of dark space existent within the original piece and the ability of that piece to translate and be discernible on the canvas I was to project upon. The second, the piece that was presented, I leaned all the way into what it was that struck me when I made the first site visit.

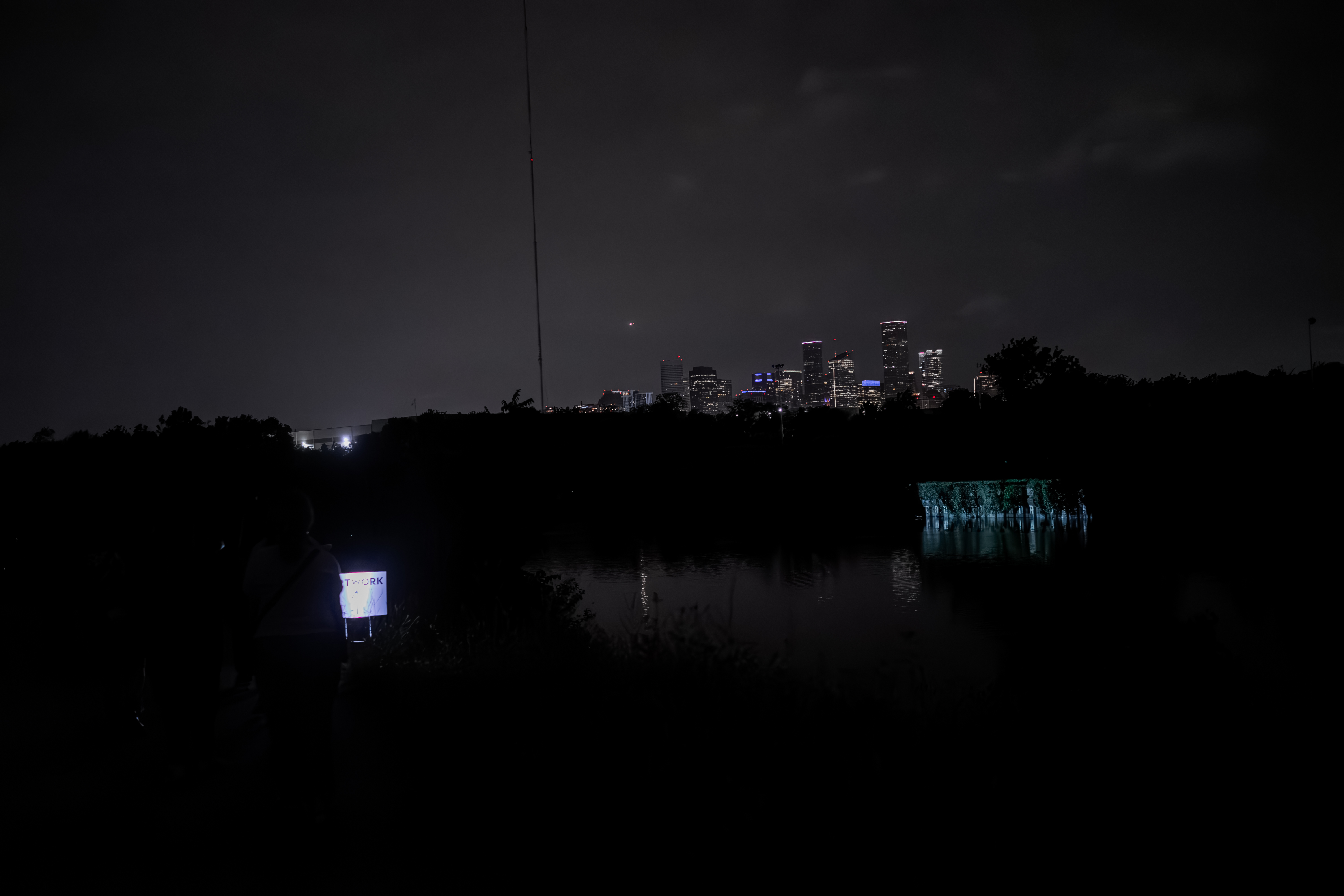

Cross No Horizon, my installation, which the public previewed during Night Light 2024, was a marquee of a digital stencil through which images sourced from the news stories, documentaries and YouTube videos depicted many migrants preparing for, boarding and riding the train through various landscapes. Above the marquee were the subtitles correlated to the speakers and subjects of the interviews and documentaries.

I especially appreciated the space I was awarded as the skyline shown in the peripheral added to the context. But even more so, due to the fact that your line of sight would be aimed directly at one of the locations where many migrant children, who were separated from their parents during Donald Trump’s presidency had been housed just outside of Downtown Houston. I felt this was especially poignant as one of the subjects of the documentaries, and subsequently, my installation was actually housed here in Houston after surrendering himself to authorities at the border.

If I may be frank, the entire time I worked towards creating and completing this work, I felt as though I was not the right person to share their stories, that my not being an immigrant, not being a part of the Latin American diaspora would disqualify my presenting the work. And honestly, I still feel this way to an extent. However, I love my undocumented friends and community members more than I could express and I, more than anything, wanted to be able to express that love by being an advocate for them and those like them by incorporating their stories in my work. They are a part of me, they make me better and I would do anything to make them feel safe, seen and welcome and that is why I made this work. I have the capacity to love and the willingness to share that love and am not afraid to openly express my love for them even if our government or certain citizens do not.